(This article is republished with permission of Patrick McCarthy Hanshi. This is the first in a series selected by Bujin.tv for special feature due to their significant contribution to the study of fighting arts. Source link: https://irkrs.blogspot.com/ )

[ View all his videos on Bujin.tv here - https://bujin.tv/profile/18 ]

Without official documentation, reliable historical testimony or conclusive evidence to explain the precise origins and evolution of Okinawa’s empty-handed fighting arts, much of their history is based on unchallenged anecdotal references, as fact. Having questioned various aspects of this diverse history [Bubishi, Koryu Uchinadi Vol #1 & #2, My Art of Karate, and Tanpenshu, etc.] the presentation which lies before you represents a combination of personal insight and empirical experience, which I hope might challenge accepted beliefs.

With the exception of historical commerce with SE Asia, a little informal testimony from foreign visitors during the later part of Okinawa's old Ryukyu Kingdom Period, and a brief mention in George Kerr's book [Okinawa, An Island People; "... boxing (Karate) in which both hands and feet are used had come from Indo-China or Siam.” p217] there's just not a lot of published research available on the relationship between Te [手] [aka Ti/Di, Ti’gwa/手小 and or Okinawa-te/沖縄手] and Siamese boxing.

*Karate enthusiasts should note that Cambodia, Laos, Burma, Siam, and Vietnam were, to varying degrees, historically influenced by China and Indian culture, prior to the time of Western colonialism; hence, the name, Indo-China.

*The Ryukyuan language is characterized by the existence of both prefix and suffix for diminutives; i.e., pertaining to or productive of a form denoting familiarity and affection... also triviality or smallness. The prefix is “guma” and the suffix is “gwa.” Both guma- and -gwa function to create diminutive words drawn from the base word. For example, in the case of old practices such as Kata and Ti, the suffix “gwa” was commonly used to denote familiarity and affection rather than triviality or smallness.

I am inclined to agree with Kerr’s observation and believe that Ti-gwa [手小]—–defined as the striking portion of Okinawan Karate—–comes down to us from old-school Siamese boxing [aka Muay Boran] and not kung fu [i.e. Quanfa/拳法], the fighting art I have previously identified as the original Chinese source from which kata/型 came.

Passion to vocation

Between the late 1970’s and early 1980’s I spent considerable time and effort reading all I could find on the history of the “Okinawan" fighting arts. I was fascinated to discover that much of Okinawa’s so-called native fighting arts had actually come from surrounding cultures (i.e., China, Japan and SE Asia). Understandably, the passion to better understand this diverse history prompted me to look into the fighting arts of its neighboring cultures.

During that research it became evident there were gaps in Okinawa’s fighting arts history... information most likely lost in the sands of time, if even recorded in the first place! Ninety-four year old Kinjo Hiroshi, noted historian, best selling author and Okinawan Karate master, explained to me that, “in spite of the importance we place upon studying the origins, history and lineage of this art today such was not the case during Okinawa’s old Ryukyu Kingdom Period.” In fact, according to Kinjo, and in spite of the anecdotal references to “a liaison with [Fujian] China,” there never has been a definitive explanation for the history of Okinawa’s empty hand fighting arts!

During the dawn of the 20th century local Okinawan authorities decided to take out from behind closed doors their secretive empty-handed fighting arts, and introduce to the public domain (albeit with an ulterior motive) a modified version of kata as a form of physical fitness, ostensibly to serve school children. With a need to fill in the historical blanks, and no official source from which to corroborate information, local enthusiasts drew liberally upon anecdotal reference to describe its origins: “Karate traces its historical origins back to China!”

Vocation to Profession

As a young man I became so passionate about the fighting arts that all I could dream about was devoting my life to its practice and someday traveling to its source of origin to live and study. I began to live my dream in 1974 when I started a career as a professional instructor. Then, during the mid-1980’s, I finally fulfilled the second part of my dream when I migrated to the ‘Land of the Rising Sun.’ What better place to walk in the footsteps of the pioneers, who had developed this fighting art, than at its source of origin?

Cultural Differences

With ample opportunity to meet and practice with so many local Okinawan authorities I made good use of every occasion and gained important insight to the art I was so passionate about. Most interesting, however, was the unusually warm and friendly attitudes I encountered everywhere in Okinawa, and throughout all of Japan, too. We all meet “nice people” here and there on our journey through life but to encounter an entire culture of such amicable people was, truly and without question, a deeply thought-provoking/life-altering experience. In fact, such a unique cultural trait really helped remove any threat to my personal insecurities and allowed me to enjoy life in a way that I’d never before experienced here in the West. Although it took some time to fully grasp that incredibly friendly social phenomenon, I ultimately come to understand that this amicable social trait was what the Japanese call, “Tatemae.”

*Tatemae/建前 literally "façade;" the behavior and opinions one displays in public. Tatemae is what is expected by Japanese society and required according to one's position and circumstances.

*Honne/本音 contrasts Tatemae and represents a person's “true feelings” and desires. These may be contrary to what is expected by society or what is required according to one's position and circumstances, and they are often kept hidden, except with one's closest friends.

East vs West

Questioning anything and everything we don’t understand is a widely accepted practice here in the West. In fact, critical thinking represents a widely accepted problem-solving tool in business, education, sports and life in general. Such an open-minded approach, however, is not the accepted practice in Japanese culture. Nowhere is this mindset more evident than within the traditional institutions of Japan; education, government, banking, the military, law enforcement, sports and other cultural activities [e.g. Budo]!

Knowing what I now know about Japan’s homogeneous, male-dominated, and discriminatory culture of conformity, I am more comfortable understanding how and why such behaviour is so widely accepted. Admittedly, the prevailing inflexibility, cultural naivety and lack of genuine inquisitiveness initially came as a surprise to me. It did, however, finally explain why its anecdotal references could have remained unchallenged and, for the most part, survived intact. Myth, a minefield of misunderstanding, the absence of critical thinking, and political protectionism all have served to further obscure the eclectic history of Okinawa’s fighting arts.

The Sum Total of its Parts

Patrick McCarthy

Patrick McCarthy

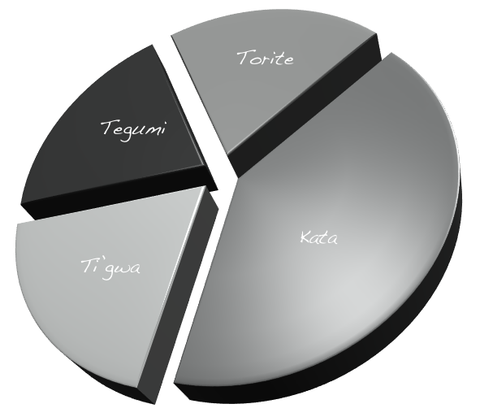

Cross-referencing such individual practices with similar yet older fighting arts from neighbouring cultures, I was able to make some interesting deductions. In spite of the ambiguity shrouding the haphazard fusion of these fighting arts brought together under the name, “Karatedo” [空手道 est. 1933], I identified no fewer than four separate disciplines. I believe that these empty-handed fighting arts represent the true source from which Karate traces its origins:

Tegumi [手組] was originally a form of grappling dating back to the time of Tametomo [11th century Japan]. The discipline is believed to have been originally derived from Chinese Wrestling [Jiao Li/角力 from which comes Shuai Jiao/摔角 --- new name est. 1928] and evolved into a unique form of wrestling before finally became a rule-bound sport called Ryukyu/Okinawan Sumo.

Torite [Chin Na/Qinna/擒拿in Mandarin Chinese] is the Chinese Shaolin-based method of seizing and restraining an opponent. Once vigorously embraced by law enforcement officials, security agencies and correctional officers during Okinawa's old Ryukyu Kingdom Period, the solo re-enactment of this practice can be found in Kata.

Kata [Hsing/Xing 型/形 in Mandarin Chinese], in spite of its vigorous local cultivation during Okinawa’s old Ryukyu Kingdom Period [see my Kumemura theory], are solo fighting routines which trace their origins back to [Fujian] Chinese quanfa [拳法]; e.g. Yongchun Crane Boxing, Monk Fist and Southern Praying Mantis styles, etc. Used as forms of human movement, and unique ways of personal training, they were popularized by the Chinese as ways of promoting physical fitness, mental conditioning and holistic well-being.

Ti'gwa [手小] was Okinawa's plebeian form of percussive impact—–aka "Te," “Ti,” "Di" [手 meaning hand/s] or Okinawa-te and Uchinadi. It was an art that depended principally upon the use of clenched fists to strike an opponent [in contrast to the open hand method preferred by Chinese arts, according to both Kyan Chotoku & Miyagi Chojun] although the head, feet, shins, elbows and knees were also favoured.

In spite of its obvious focus upon striking, physical conditioning and the art of fighting, Ti’gwa also placed considerable emphasis upon character development, as exampled in the advice left by a 17th century Ryukyu statesman named Tei Junskou [程順則]:

“No matter how you may excel in the art of Te, and in your scholastic endeavours, nothing is more important than your behaviour and humanity as observed in daily life.”

Tei Junsoku [1663-1734] was a Confucian scholar and government official of the Ryūkyū Kingdom. He has been described as being "in an unofficial sense... the 'minister of education'", and is particularly famous for his contributions to scholarship and education in Okinawa and Japan. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tei_Junsoku

Indo-China

Satisfied that I had successfully located the original sources from which came Tegumi, Torite and Kata, my efforts to trace the origins of Ti’gwa proved a bit more challenging. Exhausting my search of Chinese, Korean and Japanese sources, and considering the possibility the plebeian art may have evolved indigenously, I remembered Kerr’s comments and was pleasantly surprised to learn that for more than a thousand years both China and India had influenced the development of local fighting arts in SE Asia. Henceforth I widened the scope of my study. In spite of the many remarkable fighting traditions I found in Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines, etc., none seemed to resemble the simplicity of Ti’gwa. The only other culture in which I could locate a tradition of similar qualities, within reasonable geographical proximity and contemporary historical timeframes, was the old Kingdom of Siam and its ancient art of boxing, Muay Boran.

If it has Feathers, Quacks & Flies...it’s a Duck!

I learned that Muay Boran [lit. ancient boxing] -using the very same tools as Ti’gwa (i.e clenched fists, head, elbows, knees, shins and feet)- was hugely popular especially during Thailand’s old Kingdom of Siam Period. Adding to the plausibility of this theory, I also discovered that Ryukyu ships had vigorously plied the waters between the two cultures, conducting a bustling commerce, for more than two hundred years during the old Ryukyu Kingdom Period! While all this seemed quite promising at the time, I still had a problem seeing the link between Muay Boran and Ti-gwa.

At first glance the differences appeared obvious; after all, everyone knows that the Kingdom of Siam became The Kingdom of Thailand and Muay Boran became Muay Thai [Kick boxing]. Muay Thai, in its modern form, looks nothing like modern sport Karate, and vice-versa! Try as I might, I still was having difficulty reconciling the precise simplicity of kumite and dynamic elegance of kata performance with the modern sport of Muay Thai! Perhaps I was focusing too much upon Thai fighters dressed in silk boxing trunks, wearing gloves, a liberal rubbing of pre-fight liniment and wailing on each other in a ring, which allowed knees and elbows!

Western Pugilism

Before forming any deductions, let’s first take a look at the link between old-school Western bare-knuckle pugilism and its modern counterpart, boxing. With a history of development not completely different, in principle, to the Muay Boran-Muay Thai transition, it is easy to understand and I believe the analogy will go a long way in supporting this presentation.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries bare-knuckle pugilism enjoyed popularity in England, Europe and the United States. There were few rules, however, and pugilists were free to employ any number of "dirty tricks" such as gouging the eyes, grabbing the hair while punching the head, striking below the waist, etc. Moreover, there were no weight divisions, boxing ring standards, time limits, mouthpieces or rules, as we know them today. Bouts frequently featured standing clinch-style grappling, head butting and throws and contestants typically stood toe-to-toe exchanging blow-for-blow. Not unlike Muay Boran, pugilists also found advantage using sweeps, elbows, knees, and choking. The odd bit of biting and spitting was not uncommon in pugilism, nor was hitting or kicking a downed opponent.

Rules Change the Game

Things began to change in 1743 when, after killing a man in a bout, English pugilist Broughton developed a set of simple rules. Broughton's rules still allowed a lot of "dirty tricks" which were considered to be just part of the sport. He emphasized that no contestant should strike a downed opponent, or seize him by the ham, the breeches, or any part thereof below the waist. Also, that an opponent on his knees was to be regarded “as downed.” Renowned fighters of his era included “Gentleman" John Jackson and Daniel Mendoza; the later being known as a small man during an age with no weight categories. Mendoza was also known for his advanced footwork and body movement to avoid, "trading blows;" something with which “Gentleman” Jim Corbett would later be credited for having revolutionized the sport.

With the development of rules (specifically the Marquess of Queensbury Rules established in the mid-1860's after the ‘London Rules’) the old art of pugilism was transformed. The new use of gloves over bare-knuckles even prevented holding an opponent by the hair and striking him! It also reduced the possibility of gouging, or using one’s thumbs and fingers to injure the opponent’s eyes. Prior to timed-rounds it was not uncommon for a round to end whenever a fighter hit the dirt or canvas. This is how matches could sometimes last up to 80 or more rounds, each varying in time duration. Also, as various throws had been used widely in the old art of Pugilism, so too were provisions made to prohibit grappling and takedowns. Elbowing and kneeing were also prohibited as was biting, spitting, eye-gouging, and striking or kicking a fallen opponent. By removing the old art’s combative elements and making gloves mandatory the new rule system changed the practice considerably.

Provisions, which promoted fair and impartial refereeing and promised fighters a percentage of the gate money, were acknowledged as the final barriers in transforming bare-knuckle pugilism into the sport and entertainment it has become today.

Muay Boran [Ancient Boxing]

No one knows exactly when Muay Boran [ancient boxing...aka Siamese boxing] was first developed. It is, however, arguably accepted that a haphazard fusion of various Chinese and Indian fighting arts had evolved in Buddhist Temples throughout the mainland of SE Asia over a period of two thousand years. By the mid-13th century Muay Boran was considered a high art form and ultimately a celebrated activity in the Royal Court of Siam. Throughout the history of Siamese culture disputes of national importance were frequently settled by armed or unarmed duels. Such was the case in 1411 following the death of King Sen Muang Ma, of Chiangmai, when his two sons, Prince Yi Kumkan and Prince Fang Ken, fought for the throne. After long and fruitless personal conflict they agreed that the issue could be resolved through single combat between their two best Muay Boran fighters.

Some believe that Muay Boran became a desirable form of unarmed combat, probably also used by Siamese soldiers if and when a weapon was lost or broken in battle. Such became its reputation that Siamese Kings began to send their sons to study the art in seclusion with temple monks; it was believed that the courage, fitness and wisdom gained from such training would create brave and wise rulers. During the dawn of the 17th century King Narai enjoyed the practice so much that it soon became know as the “Sport of the Kings.”

When the ancient Siamese capitol Ayutthaya fell to the Burmese in 1767 the invading army rounded up thousands of Siamese prisoners, among whom were a number of Muay Boran fighters, and took them back to Burma, where they remained for years. In Rangoon on the 17th of March 1774, the Burmese hosted a weeklong religious festival in honor of Buddha. Amidst the festivities King Hsinbyushin [aka “King Mangra” by the Siamese] petitioned Burmese Lethwei [box-ing] fighters to compete against the captive Siamese Muay Boran fighters. A Siamese fighter named Nai Khanomtom was selected to fight the Burmese champion in front of the King’s throne.

Performing the traditional Wai Kru pre-fight dance to pay his respects to his teachers, ancestors and the spectators, Nai Khanomtom perplexed the Burmese, who thought it was black magic. When Nai Khanomtom defeated his opponent quickly the Burmese referee immediately declared the knockout invalid because their champion was too distracted by the “black magic.” This resulted in Nai Khanomtom fighting nine more Burmese champions in order to prove himself, with no rest between matches.

The Burmese King was so impressed with his courage and skill that he granted Khanomtom his freedom and allowed him to return home to Siam, where he became a hero. Nai Khanomtom was subsequently hailed as, “The Father of Muay Boran,” and from that time, the 17th of March became known officially as ‘Muay Boran day,' in Siam [Siam became Thailand in 1939].

Muay Boran Rules

As the ancient bare-fist art of fighting became popular as a sport among the Siamese people so too did competition grow. To protect their hands and inflict the maximum damage to an opponent’s face competitors bound their hands and forearms with lengths of horsehide. Horsehide was ultimately replaced by hemp rope, which was soaked in glue before being tied around the arms to create the strongest reinforcement. In the case of important matches, and with the agreement of both contestants, ground glass was sometimes mixed in with the glue, which understandably made for bloody battles! Originally, there were no weight divisions, boxing rings, time limits, mouthpieces or official rules as we know them today, and bouts frequently featured standing clinch-style grappling, head butting and throwing… and fighters typically stood toe-to-toe exchanging blow-for-blow. The only protective equipment worn was an optional groin guard made from tree bark and/or local seashells. It wasn’t until the mid 19th century that this style of fighting gradually began to change. By the early 20th century time limits, boxing gloves, standard costumes and an official set of uniform rules were introduced for amateur and professional competition.

Many who study the history of Muay Thai understand that forces not unlike those which affected the evolution of Western Pugilism also played an important role in the transition from the old-school bare-knuckle art of Muay Boran to the modern sport of Muay Thai. - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N0GBQyQnuJ4

Unanswered Question

Having established plausible explanations for three of the four original sources to which the art of Karate traces its origins [i.e. Tegumi, Tori-te & Kata], the question remains unanswered as to whether or not Ti’gwa is simply Okinawa’s local interpretation of Muay Boran dating back to a time before its modern transition. Like Tegumi, Tori-te and Kata, could Ti’gwa have been simply yet another foreign import? Could this plebeian form of bare knuckle fist fighting have found its way to Okinawa during the more than two centuries of bustling commerce it enjoyed with the old Kingdom of Siam? Not only do I believe it did, but I am also confident that the combination of time, cultural forces and varying outcomes are responsible for its transformation. Before making a final conclusion let us look at these issues.

Cultural Forces

There’s little doubt in anyone’s mind that the modern Japanese tradition of Karatedo [空手道] comes to us directly from its Okinawan predecessor Karate-jutsu [唐手術]. The introduction and subsequent popularization of the Okinawan art on Japan’s mainland is also documented and requires little discussion. The same can be said for those local Okinawan instructors [e.g., Motobu Choki, Funakoshi Gichin, Miyagi Chojun and Mabuni Kenwa, etc.] most responsible for pioneering its introduction, along with the 1st generation Japanese recipients [Ohtsuka Hironori, Konishi Yasuhiro, Yamaguchi Gogen and Sakagami Ryusho, etc.]. Memorable names permanently entrenched in the annals of this art’s history make it possible to more closely study and fully understand its modern transition. A few points, however, which may not be as well known, and could certainly shed important light upon these issues, should also be addressed:

- The name “Karatedo” [空手道/empty hand way] is a modern term not developed until 1933. Prior to this Karate in Okinawa, had been referred to as, Ti’gwa [手小/hand], or just Ti/Di [手]. The term Toudi [唐手/also pronounced Karate, meaning Chinese hand] or Toudi-jutsu [唐手術/the art of Chinese hand] was also common, but used largely to differentiate between the plebian bear knuckle Ti’gwa and Chinese quanfa [拳法/kenpo in Japanese] … the original source from which came kata.

- In some circles it is believed that the Karate originally introduced to the mainland of Japan was not representative of the entire original empty-handed fighting art, but rather only one part [Kata] of a larger whole; that missing the practices of Tegumi, [grappling], Tori-te [seizing and controlling an opponent] and Ti’gwa [percussive-impact]. There is, of course, a plausible explanation for this.

In support of Japanese National Polity [Kokutai no hongi/國體の本義], and the 1898 Conscription Law [mandatory military service] affecting the people of Okinawa Prefecture, former bureaucrat and authority on the local fighting art’s, Itosu Ankoh [1832-1915] spearheaded a movement to use Karate-jutsu to accomplish in Okinawa the same military-related goals that Kendo and Judo had achieved on mainland Japan. For those not already aware, it should be noted that both Judo and Kendo played a vital role in supporting Japan’s early military agenda.

Becoming compulsory adjunct activities in the physical education curricula of Japan’s school system, they served as a vehicle through which to produce an able body and a dauntless fighting spirit. Meiji Period [1868-1911] military propaganda often glamorized the practice of Budo as, “the way common men built uncommon bravery." Up until the end of WW2 Japanese fighting arts in the school system served well to ready conscripts for its war-machine.

Modifying the practice of kata, Itosu Ankoh created a simplified version of the Okinawan art to be used exclusively in schoolyard exercise. In this way the simplified kata could easily be used as an effective vehicle through which to funnel both physical fitness and social conformity. In doing so, he not only succeeded in supporting the national agenda he also brought considerable recognition to the tiny island culture.

Understandably, much was lost when Itosu Ankoh brought out from behind closed doors the old practices and introduced a simplified version to the public domain through kata. It was during that era that many of the original Tegumi, Tori-te, and Ti’gwa practices began to fall quietly dormant as the overall art became forever transformed.

Less is More

If less is more then there’s little question about the initiative of Itosu Ankoh in revolutionizing the practice of Karate. That said, however, today many ask, “At what cost to the original art?” Despite the losses, it might help to realize that during the late 19th and early 20th centuries there was a growing indifference toward empty-handed fighting arts, and directly connected to Western colonialism, and the sentiment was not limited to Okinawa. The appearance and widespread use of firearms during the Opium Wars, Boxer Rebellion and Chiang Kai-Shek’s destruction of the Shaolin Monastery led to the death of not only countless Chinese martial art-trained warriors [e.g. fighters/security brigades/soldiers, etc.] but also of the myth that mastering the fighting arts made one invincible!

In spite of this caveat, however, one redeeming quality the entire empty handed fighting arts had in common was physical fitness. Regarded as the cornerstone of health and well-being, the fighting arts were recognized as vital tools in strengthening character and national identity. Moreover, their ability to promote physical fitness and a dauntless fighting spirit, were qualities essential to the effectiveness of any military force. With wrestling and fencing having become adjunct practices in the Western school system, so too did boxing come to be considered an asset in the developing similar outcomes.

One school of thought believes Japan was merely following Western pedagogic initiative in reshaping old-school grappling and swordsmanship practices into Kendo and Judo to achieve the same desired goals. Seeing the value boxing represented, Itosu Ankoh took the initiative to recommend Karate be used in a similar way as an adjunct in the physical education curriculum of Okinawa’s public school.

3.Readers may be surprised to learn that the Karate introduced to the mainland of Japan during the 1920’s was little different from the highly repetitive, kata-dominated practice Itosu Ankoh popularized in Okinawa’s school system. Moreover, there was no sparring or application format through which students could test the veracity of their technique or measure their fighting spirit!

The absence of such a catalytic mechanism probably takes on greater meaning when readers understand that sparring was considered not only the accepted practice within traditional Kendo and Judo training, in that era it was expected. In spite of the fact that both Kendo and Judo depended upon repetition and ritualized kata, participants clearly understood that it was through the challenge of free sparring [jigeiko/地稽古 in Kendo & randori/乱取り in Judo] that their fighting skills were tested, an indomitable spirit measured and progress assured. In fact, the reason first generation Japanese Karate students began to experiment with sparring drills in Tokyo’s university clubs was out of boredom with the mindless repetition of kata and the absence of practical fighting drills. Readers may also be surprised to learn that, from the time he arrived in Tokyo in 1922, Funakoshi Gichin only taught kata; “Kata is Karate-Karate is kata.”

- Another widely misunderstood issue relates to the way kata was taught during that era in both Okinawan public schools and mainland Japanese university dojo. The idea that students first learn fundamental exercises [kihon waza/基本技] before they learn kata is accepted as today’s standard. This, however, was not true of that era! The idea of breaking kata down into smaller parts [punches, kicks, blocks, strikes, stances] to develop individual practices in support of learning kata was yet another by-product of its first generation Japanese students seeking to improve learning standards. Until the time that kihon-waza were developed in the 1920’s, kata were learned exclusively through rote repetition.

During that embryonic era on the mainland the only exception to the rule was the Ti’gwa of Motobu Choki. His approach to teaching the Okinawan art was contrary to the rote repetition of kata used in the school system and far more indicative of the old-ways. He was an outspoken opponent of what he described as fancy-looking karate which had no real substance; a fad he likened to the Shamisen [三味線]: A 3-string Okinawan guitar that is pretty on the outside but empty on the inside!

He frequently criticized any and all incongruous training methods used by his fellow countryman, Funakoshi, and openly laughed at propaganda geared towards having learners believe the true meaning of kata would or could become inherently evident by virtue of its practice! In the midst of Japan’s strict culture of conformity, Motobu Choki was expected to sacrifice personal differences for the sake of communal tranquility. A fundamental Japanese proverb reads… Deru kui wah utareru [出る杭は打たれる] and literally means, “A protruding nail gets hammered down.” By Japanese standards it means: if you stand out you will be subject to criticism. If nothing else, Motobu Choki stood out! Unfortunately, he was ultimately ostracised for such outspokenness. Sadly, during this era his old-style Ti’gwa was largely ignored by the general public.

- Karate became popular on the mainland during Japan’s radical period of military escalation. As such, the practice underwent yet another transformation due in large part to the relentless force of Japanese [Budo] culture. Elsewhere in this presentation I have cited characteristics of the Japanese mindset as being “different” from the West. For those who know little about Japanese culture, my comments could be perceived as indifferent or perhaps even promoting anti-Japanese sentiment. Such is not the case. While an entire dissertation might better describe, “the different way things are done in Japan,” I am limiting my explanation to a unique cultural phenomenon known as Shikata [仕方]. Literally the form and order of doing things in Japan, "kata" [方] is the cultural conditioning that causes the Japanese to think and react in the way they do. For readers who require more information about Shikata, I recommend Boye De Mente’s excellent publication, “Kata: The Key to Understanding and Dealing with the Japanese.” For more see here http://tinyurl.com/3gwht6j

As the new and foreign [i.e. not yet Japanese] fighting art began to gain momentum on Japan’s mainland, the prevailing mindset representing Japanese Budo [of which Karate was seeking to become an integral part] compelled Okinawan instructors to observe cultural etiquette and accept established protocols without question. From the time Karate arrived on the mainland in the early 1920’s until the time it was officially recognized as a part of Japanese Budo a decade later, the fighting art underwent significant transformation.

The principal changes to “Kara-te-jutsu [唐手術] included eliminating both the prefix and suffix ideograms, which revealed both its foreign origin and “antiquated” objectives. The old ideograms were replaced with descriptions more befitting the practice and cultural mindset: 空/Kara meaning ‘empty,’ and 道/Michi or Doh meaning ‘path’ or ‘way’.

In addition to these changes came the adoption of a standard training uniform [着/gi], the use of the belt [obi/帯], and the rank system [段-級/dan-kyu] borrowed from Judo/柔道 with the blessings of its founder, Kano Jigoro [嘉納治五郎]. The transition became complete when Karate finally established a competitive format. Described as Ippon Shobu [一本勝負/one-point match] and based largely upon the “kill with a single blow” theory [ikken hisatsu/拳必殺] prevalent in Kendo [剣道] and Judo [柔道], Karate enthusiasts were finally able to test their physical technique and measure their fighting spirit.

- Karate-do[空手道] having both conformed to the expectations of Japanese [Budo] culture and fused together the newly developed kihon-waza practices in support of both kata and kumite, the Dai Nippon Butokukai [大日本武德會] officially recognized it as a modern fighting art [Gendai Budo/現代武道] and part of Japanese Budo [日本武道] in December of 1933. It may be interesting for readers to note that, in spite of its diversified heritage, Karate was created as a unified tradition without styles, in the same way that Kendo and Judo had been transformed from previously existing practices. With a look and feel completely unlike its Okinawan predecessor, the new tradition had become uniquely Japanese. Emphasizing the newly developed solo Kihon drills, rote repetition of stylised Kata and rule-bound Kumite, herein lies the template from which “3K-Karate” would find its way to the four corners of the world.

Catalytic-like Mechanism

Understanding how rules and varying outcomes helped bring about change in both Western pugilism and Siamese boxing, it becomes less difficult to see how such influences also impacted the evolution of Karate-jutsu. As rules so often dictate the means by which athletes best achieve competitive outcomes, it makes sense that training methods developed during the 1920’s and 1930’s reflected contemporary goals. Even though a considerable portion of the changes which transformed the old Okinawan art were cosmetic and recreational, by looking more closely at this embryonic period we discover two powerful catalytic mechanisms: The omnipotent force of Japan’s unique character along with its inescapable pre-war military agenda. Herein lies the principal factors which best explain this metamorphosis.

It is sometimes said that Budo [of which Karate is an integral part] is a cultural microcosm (i.e. a miniature representation of the beliefs and social behaviors of the people and culture from where it comes). As such, I believe it is possible to learn much about the people and place from which the art comes by looking beyond our physical training and into its unique history and fascinating culture. A Japanese saying, as provocative as it is informative, goes...On Ko Chi Shin [温故知新]; “Study the old and understand the new.” Another ancient proverb, equally as educational, reads, Bun Bu Ryo Do [文武両道]. Usually described as the twin paths of the Pen and Sword, its deeper meaning reveals a dual balance between fighting art and culture. I am confident that, reflecting this timeless wisdom, one’s life can be as much a product of the art as the art is a product one’s life.

More Questions

There were actually two other points I had intended to address concerning the matter of style [Ryuha/流派] and influence. As the original art addressed the kind of violence not bound by rules, I wondered if commercial profit, self-serving agenda and cultural protectionism have had much to do with the propaganda promoting a general acceptance of practices so limited by style? Also, because there seems to be so much emphasis these days placed upon going to Okinawa to get the “authentic” or “original” versions of this art, I had been hoping to measure the influence that modern Japanese Karate has had back upon the subsequent growth and direction of this tradition in post-war Okinawa. Perhaps, however, I’d best leave these for another time.

“Where’s the Forest?”

“Can’t see the forest for the trees,” is a classic expression which best describes anyone who is so involved with the tiny details of something that they neglect to see or even realize that there’s something more ...including its original purpose. For example, when focusing so intently upon little things of one’s style such as, “the way ‘we’ do or don’t it,” “our dojo,” “my sensei,” “it’s not our rules,” “oh, we don’t do that...” it’s not a forward stance...it’s a back stance,” “it’s not a 42 degree angle punch—it’s a 45 degree angle punch!” etc., the concepts and outcomes of the original art itself are often overlooked, if ever understood in the first place! Losing site of the larger issues, which define its original purpose, and functional practice means the beauty and depth of this wonderful heritage may never be accurately understood.

Conclusion

That the theory presented in this work is not corroborated by past or present generations of Okinawan Karate authorities doesn’t make it any less valuable. The lack of official documentation, historical testimony and conclusive evidence explaining the eclectic origins and subsequent evolution of Okinawa’s empty-handed fighting arts was more than enough to provoke my curiosity. I have questioned the accepted history and origins of Karate, provided compelling evidence to identify its individual domestic and foreign precursors, and arrived at a perfectly plausible explanation of the forces, which shaped its transitions.

I am satisfied with the results of this study and sincerely hope my presentation has succeeded in illustrating how and why Muay Boran [i.e., Siamese Boxing] represents the original source from which came Ti'gwa. More importantly, I hope this modest work might also serve to open new doors of opportunity. Perhaps even inspire readers to think outside the box and feel comfortable knowing that critical thinking remains an acceptable and important tool in helping to eliminate the terrible ambiguity, which shrouds the history of this art.

Deep roots strengthen the foundation of this art and yet wings provide the means to continue forth on the journey of discovery. Practicing Karate links us inconspicuously to its past; through discipline and sacrifice we discover our inner-self; by training together we forge important bonds of friendship and by living the art we honor its heritage, which in turn keeps this spirit alive. Tradition is not about blindly following in the footsteps of the old masters, or even preserving their ashes in a box, but rather in keeping the flame of their spirit alive, by continuing to seek out, understand and improve what they originally sought. I am confident this thinking is far more in line with the original approach, intentions and teachings of the pioneers than is the conformist mentality in which this art’s progression has fallen dormant.

Liking the art of Karate to a pathway, and paraphrasing the wisdom of the great Zen Master Basho, it depends how far down the path one travels before it starts to become evident that the destination is not the goal, it's the journey.